Today people have access to a wide variety of technologies that allow them to enjoy themselves more, understand things better and which generally make life easier. Among the institutions that potentially stand to benefit most from these technological advances are museums, although the unfortunate – if not downright unfair – irony is those in the public sector are least able to afford them.

Even though funding issues are a major obstacle to utilising modern techniques for displaying artefacts and enhancing exhibits, museums are taking advantage of technology to bring art, history and other subjects alive wherever possible. Right now the key technologies – or at least the most aspirational – are seen as interactive exhibits, which covers augmented reality (AR)/virtual reality (VR) and virtual production in general, including 3D holograms; interactive display cases, monitors, kiosks and displays; multi-touch walls and screens; immersive audio; next generation image and video projectors; custom floors with trigger sensors; and software and mobile apps to convey information, often to visitors’ own devices.

LASER SYSTEMS

In addition to these, Andreas Will, project manager at interactive technology developer Garamantis, highlights laser-based systems for reading hand movements, interactive projectors and projection mapping. This last area involves using non-regular objects and surfaces, such as walls and floors, instead of traditional screens for video and image projections. These, together with other techniques, were implemented in the Samurai Museum in Berlin, which opened in April 2022 and houses a private collection of armour, weapons and other items from the warrior and feudal era of Japanese history.

“The exhibits include an interactive cinema that can accommodate eight to ten people – children in particular – whose hand and arm gestures are recognised by a laser tracking system that trigger projections showing specific characters from Japanese folklore,” Will explains. “By gesturing at each figure, you can win points as well as getting information about them, so its a combination of a multiplayer game with historical facts. There are also a lot of interactive touch screens, which allow visitors to zoom in on an original artefact that is behind glass in a case, and also projection mapping on to the wall, displaying things like a 3D printed block of metal, which illustrates a selected period of history.”

Will acknowledges that because the Samurai Museum is privately funded, there was more freedom to use interactivity and other state-of-the art techniques. However, he adds, these technologies are also being used by public museums to push the boundaries of how to exhibit and examine a particular moment in history. A recent example is Everyday Life in Times of Crisis – Crisis Communication during the Pandemic, which ran at the Berlin Museum of Communication from July to October 2023.

Commissioned by the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) and featuring displays and visuals developed by students at the Berlin School of Design and Communication, the exhibition featured a multi-touch table and a 360-degree rotating multi-touch screen. These were used to deliver a timeline of the pandemic and scientific findings from the BfR.

“We wanted to present what was a difficult subject in an easily acceptable way,” says Will, “so we created a timeline from the beginning of the crisis until today, with AR displays changing at different points to show not just the scientific information but also the news of the time and the social media conversation showing what the public was going through.”

REACTIVE INSTALLATIONS

While the term ‘interactive’ is commonly used in relation to modern displays and exhibits, many installations are what could be termed ‘reactive’. This is the case with museum projects undertaken at the moment by hologram specialist Musion 3D.

Company director Ian O’Connell observes that the most common implementations involve footfall triggers and motion sensors to activate a hologram or display. “But we are on the precipice of being able to allow someone to go up to an avatar and verbalise a question that is ingested into ChatGPT, which then produces an answer for the metaverse character or avatar,” he says.

Musion offers visual display platforms, including EyeLiner Foil, a holographic projection system described as a modern version of the old Pepper’s Ghost theatrical trick. It comprises a ‘performer’s stage’ with LED lighting and a polymer screen that sits on a 45-degree angle between the stage and the audience. Also available is EyeCandy, a smaller EyeLiner, and the Holoconnects Holobox, essentially a hologram within a clear screen, which Musion represents for hire and sale in UK, Europe and Asia.

Musion offers visual display platforms, including EyeLiner Foil, a holographic projection system described as a modern version of the old Pepper’s Ghost theatrical trick. It comprises a ‘performer’s stage’ with LED lighting and a polymer screen that sits on a 45-degree angle between the stage and the audience. Also available is EyeCandy, a smaller EyeLiner, and the Holoconnects Holobox, essentially a hologram within a clear screen, which Musion represents for hire and sale in UK, Europe and Asia.

Once a hugely expensive technology, holograms are now coming within the reach and budget of museums. “The cost of producing a hologram has come down from tens of thousands of pounds to hundreds of euros,” says O’Connell. “The art of human animation will grow like CGI did, from its beginnings on Jurassic Park and Toy Story. There will be aural, verbal inputs [for avatars] and people will be able to interact with them using mobile apps.” He adds that artificial intelligence (AI) will also “most likely manifest itself in museums.”

AI POTENTIAL

The potential of AI is not only in producing more detailed and specific information but also, as Will Bullins, executive consultant at systems integrator Electrosonic, explains, a higher degree of personalisation.

“AI is obviously a huge piece of the future of technology and interaction,” he says. “Traditionally, a guest walks up to an exhibit and interacts with a display, which goes through a series of presets to tell a story. The thrilling aspect of AI technologies like ChatGPT lies in their capacity to understand language and human intent. With AI, we see the ability to tailor an experience to each individual guest based on their preferences and what they are interested in, creating a unique experience for the individual.”

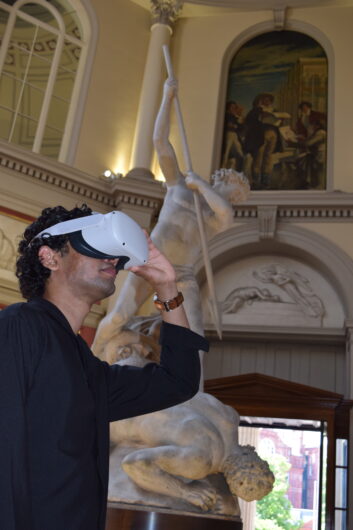

Among the technologies making in-roads into museums, Bullins highlights touch screens – or devices using sensors for lidar (light detection and ranging) or motion detection and BYOD (bring your own device) – as becoming more popular for interaction. “VR is being used but it’s hard to do right and some guests don’t want to wear headsets or put themselves in the spotlight,” he says. “Informational overlays with AR are great and you can use your own phone to learn more about an exhibit just by pointing your camera at it. It is also a fun way to see more than what is on display because many museums have many exhibits or artefacts that are in storage.”

MUSEUM DEPLOYMENT

Jack Ridley, sales account holder at self-service and interactive kiosk developer imageHOLDERS, observes that virtual technologies, such as avatars and AI, are increasingly being deployed across museums.

“Such fun and interactive experiences are being used for the likes of superimposed images, adding explanations and sound and vision,” he says. “These enhancements are enabling museums to stay up-to-date with customer expectations, making the experience more accessible and engaging.”

Ridley is of the opinion that interactive technologies in museums are “definitely becoming more standard”, with the ability to transform spaces by adding immersive audio and enhanced visuals as well as AI/avatar experiences. From imageHOLDERS’ perspective, he adds that interactive kiosks can be used in a variety of ways. “They can offer an enhanced user experience to learn about, for example, dinosaurs, with a touch screen allowing people to select facts and find out more,” he says. “Interactive screens can also provide VR environments able to transport the user to moments in history.”

Ridley is of the opinion that interactive technologies in museums are “definitely becoming more standard”, with the ability to transform spaces by adding immersive audio and enhanced visuals as well as AI/avatar experiences. From imageHOLDERS’ perspective, he adds that interactive kiosks can be used in a variety of ways. “They can offer an enhanced user experience to learn about, for example, dinosaurs, with a touch screen allowing people to select facts and find out more,” he says. “Interactive screens can also provide VR environments able to transport the user to moments in history.”

Outside influences are always important for promoting new technology and films and theme parks are now further pushing museums into new experiential areas. “Visitors have come to expect world class experiences,” agrees Jason Larcombe, strategic project manager at extended reality (XR) and virtual production specialist White Light, now part of d&b solutions.

“Large commercial organisations, such as Warner Bros, Disney or more recently, Outernet, Lightroom and Frameless, have all reset the expectation for exhibitions, providing highly immersive and relatable experiences,” he goes on. “They are using interactive technologies to generate a new language for what should be synonymous with exhibitions and presentations. In doing so, they are setting new benchmarks.”

Part of this, Larcombe continues, is to make the visitor less a passive observer merely absorbing facts and more part of the exhibit itself. “Interactive displays give the visitor agency, by being able to choose how and what they see,” he explains. “They also allow personalisation when used in conjunction with camera tracking and AI solutions. For example: you can stand in front of a screen – which acts as a mirror – and the screen will show you wearing a costume. These techniques have proven successful in fashion and experiential outlets and are slowly coming across to the museum world.”

AUDIO FACTORS

While attention is focused primarily on what virtual and visual technologies can bring to museums, sound is another important factor in bringing an exhibit to life. Larcombe observes that spatial audio “can help guide a visitor through a space or present a deeper connection to a particular exhibit and immerse a visitor in an experience”. This was the intention with DaVinci: Genius, currently in Amsterdam as part of a European tour, which presents the multifaceted brilliance of Leonardo DaVinci in an immersive, interactive exhibition and features a d&b audiotechnik Soundscape 3D audio system.

Sennheiser has been involved with spatial sound in the form of Ambisonics for some time and has just begun working with the technology to create what it describes as “true audio environment recreations”. Josh Lefkowitz, business development manager for the US northeast region at Sennheiser, comments that BYOD is a major factor for museum interactivity in general and on the sound side in particular. This is illustrated by The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, which is using a customised version of the Sennheiser MobileConnect iOS and Android apps. This enables visitors to stream audio on to their phones that syncs with video and film art exhibits in MoMA.

Sennheiser has been involved with spatial sound in the form of Ambisonics for some time and has just begun working with the technology to create what it describes as “true audio environment recreations”. Josh Lefkowitz, business development manager for the US northeast region at Sennheiser, comments that BYOD is a major factor for museum interactivity in general and on the sound side in particular. This is illustrated by The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, which is using a customised version of the Sennheiser MobileConnect iOS and Android apps. This enables visitors to stream audio on to their phones that syncs with video and film art exhibits in MoMA.

EXPERIENCE ECONOMY

In their 1999 book The Experience Economy, Joseph Pine and James H Gilmore outlined the ‘4Es’ of business: educational, (a)esthetic, escapist and entertainment. Alexis Reymond, sales manager of stage tracking system and show control developer Naostage, comments that museums have embraced this idea and are now offering “an entertaining, immersive and/or interactive experience”, which is resulting in higher visitor numbers. “The general trend is to increasingly adopt interactive technologies,” he says.”Although this may vary according to the type of museum and the purpose of the exhibition.”

According to Reymond, the possibilities for museums can involve virtual tours and historical reconstructions, interactive simulations and educational experiences based on AR. “As well as AR, the technologies being used may include VR immersive experiences, interactive monitors to display additional information, multi-touch walls for interactive manipulation, projections for visual presentation and customised floors for sensory experiences,” he says.

“A tracking and show control tool like Naostage K SYSTEM allows all third party systems to be managed on a single system, enabling museums to reduce their operating costs.”

CREATED ENVIRONMENT

While ‘interactive’ and ‘immersive’ are routinely used to describe what is – or can – be done with museum exhibits, the main goal, as Mark Wadsworth, vice president of global marketing at Digital Projection, observes, is to transport the visitors top a different place by putting them in a created environment. Examples of this that use Digital Projection systems are The Spirit of Japan art exhibition at the Kadokawa Culture Museum and the reconstruction of Michaelsberg Abbey in the Bamberg UNESCO world heritage site. The former used over 30 E-Vision Laser 10K projectors to light the floors, ceilings and walls of gallery, while Multi-View 3D projection was used for the latter to project images of the ‘lost’ abbey, which visitors could move around.

“Visitors want more – more experiences, immersion and lifelike representation in the exhibitions they visit,” Wadsworth says. “AV has the power to transform traditional exhibits in museums and by creating these unique experiences, the attractions bring people back time and again. In an ever more connected world where social media is critical for attracting visitors, AV can provide the backdrop and the wow-factor that propels exhibition popularity to new levels on social media and as a result, increase revenue for venues.”

Lighting is a key component in modern museums, with dvLED (Direct View LED) in particular being used for not only general illumination of displays but also interactive art exhibits. “Interaction on the canvas itself via touch is very difficult to achieve,” says Cris Tanghe, vice president of product at digital display, video wall and visualisation system manufacturer Leyard Europe.

“For this application we see dvLED solutions rising in importance. These can more easily be made interactive while still covering a large surface with a seamless image. Additionally, dvLEDs can be deployed in a variety of shapes, sizes, and resolutions, both indoor and outdoor, on floors and ceiling. This makes it the go-to solution for artistic designers and planners.”

Many museums are now not just installing technology specified by designers and systems integrators but are taking an active role in developing new systems that are shaping the future of exhibitions.

University College London (UCL) Art Museum has been involved in two such projects: the first developing VR technology in conjunction with tech start-up Kagenova, while the second and centres on touchless computer interaction developed by UCL Computer Science students.

“It is novel, touchless computing, which gives you the ability to control any computer with gesture alone,” explains Dr Nina Pearlman, head of UCL Art Collections. “This can be with the wave of an arm or the blink of an eye but also by speech. And the technology is available to download where people get their apps. We are now bringing the students that designed it into dialogue with our public programming team, audience groups and artists to see how we can push the boundaries of this technology in the context of the museum environment.”

ASPIRATIONAL INNOVATIONS

Even with such readily available innovations, Pearlman still views interactive and immersive tech for museums as aspirational. “They can mostly be found in museums and other cultural venues that are either dedicated to technology and the moving image, or have an exceptionally high volume of visitors with partnerships to industry,” she says. “Smaller museums find it difficult to sustain engagement that is based on interactive technologies at scale, due to lack of equipment and AV support staff.”

The aim with all this new technology appears not to change the nature of museums but to make what they are exhibiting more engaging and involving, while giving access to valuable or delicate items as digital twins. If that can pass the bored small child test, then the future – and the past – looks assured.