In the past, and for many years, broadcasting had a reputation amongst many of being the pinnacle of technology and technological development. The term ‘broadcast quality’ was regarded as a guarantee of excellence and still carries considerable weight today. For some, the equipment used for professional AV applications was regarded as being not on the same level. The main reason for this was cost, with the events and presentation sectors not having the same budgets as their TV counterparts.

The situation has changed markedly in the last 30 or so years. Broadcast standards have been relaxed in that time, particularly in the UK where legislation was introduced to encourage more competition in the market. On a strictly technical level, the adoption of digital and IT-based technologies – most notably IP – by both broadcasters and pro AV contractors has also levelled the field considerably. There are still differences between the two sectors, with each retaining individual requirements, but the former dividing quality lines are now hazy, and with AV and broadcast technologies converging rapidly, lines are increasingly blurred.

Technology developers that appeared during the mid-1980s and into the 90s, when the software and computer boom was beginning to influence both AV and broadcast, were among the first to see how there were techniques in the two sectors that could be mutually beneficial. “The broadcast industry has always been about the purest quality of signal possible, working uncompressed to the best standards,” comments Liam Hayter, senior solutions architect at NewTek, part of Vizrt, a developer for graphics, virtual studio and infrastructure systems for broadcast.

Technology developers that appeared during the mid-1980s and into the 90s, when the software and computer boom was beginning to influence both AV and broadcast, were among the first to see how there were techniques in the two sectors that could be mutually beneficial. “The broadcast industry has always been about the purest quality of signal possible, working uncompressed to the best standards,” comments Liam Hayter, senior solutions architect at NewTek, part of Vizrt, a developer for graphics, virtual studio and infrastructure systems for broadcast.

“Ultimately it would go out on DVB [Digital Video Broadcasting, the standard for digital terrestrial TV], which is compressed. Then there’s live streaming, which is also compressed and, generally, whenever you work with compression you want to start with something at the highest quality to deliver the best possible quality.”

Whereas broadcasting is about reaching as big an audience as possible through transmission technologies, pro AV was for a long time primarily concerned with addressing people in a specific environment. In recent years, Hayter explains, this dichotomy has changed considerably, largely because of new tech, but with the pandemic inevitably having an influence in driving the use of video conferencing.

“AV has always been more focused on the in-room experience, rather than remote contributors,” he says. “The need has been different and the people doing AV didn’t have the budget of broadcasters. But the shift to IP and software has levelled that out. Broadcasters are no longer afraid of working compressed because, for example, the film industry has gone from working with the best possible quality to using compression. That’s also bled into AV because people want to work across the internet in a networked environment. Our production systems natively allow people to run Teams, Zoom, Skype and Discord, all the major video conference platforms, even WhatsApp and FaceTime, as a live source. So you can just call in and [it’s allowed] quite an exciting space where they can be used as creative tools.”

BROADCASTING DEMANDS

Graham Sharp, chief executive of Broadcast Pix, observes that “IP/IT technology has always been used in AV” but today it is now fast and reliable enough to meet the demands of broadcasters. “Because of this it is being rapidly deployed, which in turn is making a lot of broadcast functionality available to the AV market,” he says. “Both sectors are looking for a cost-effective infrastructure that can meet the needs of today and yet scale and adapt as market requirements change. And as streaming exploded, users were searching to improve their production values beyond just feeding from a camera. Which is why so many broadcast tools have migrated into the AV world, such as camera control effects, transitions and TV quality graphics.”

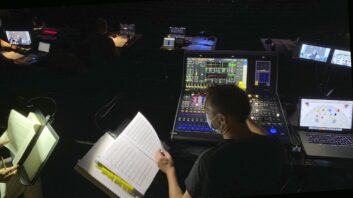

Sharp is a veteran of the broadcast market, having held engineering and executive positions at a number of companies including Tektronix, Avid, Discreet Logic and Grass Valley. While Broadcast Pix produces production switchers, a mainstay of TV presentation, Sharp has moved it more into the AV market, with systems designed specifically for houses of worship and meetings, supported by live streaming capabilities. “Most technology is now software running on CoTs [commercial off the shelf] hardware or in the cloud, so the flexibility and price point have brought many broadcast-specific tools into AV. We like to say we now serve the A to Z of video production, from aquariums to zoos. News-style graphics, professional-looking transitions and effects, remote camera control and automation are all used to make more compelling content.”

Sharp is a veteran of the broadcast market, having held engineering and executive positions at a number of companies including Tektronix, Avid, Discreet Logic and Grass Valley. While Broadcast Pix produces production switchers, a mainstay of TV presentation, Sharp has moved it more into the AV market, with systems designed specifically for houses of worship and meetings, supported by live streaming capabilities. “Most technology is now software running on CoTs [commercial off the shelf] hardware or in the cloud, so the flexibility and price point have brought many broadcast-specific tools into AV. We like to say we now serve the A to Z of video production, from aquariums to zoos. News-style graphics, professional-looking transitions and effects, remote camera control and automation are all used to make more compelling content.”

While it would be easy to assume that the direction of technologies and techniques between broadcasting and AV was one-way, broadcasters are also benefiting from systems that originated in the events and installed markets. “Broadcast technology seemed like a relatively well-defined field only ten years ago but with the general access to high definition recording, editing and processing tools now, we are seeing a greater scale of convergence and blurring of formerly clear boundaries,” comments Hans Stucken, global marketing advisor at AV Stumpfl.

The company produces projection screens and the PIXERA media server, which Stucken says is being used for in-house corporate broadcast facilities based around a ‘mini studio’. “More and more installations feature aspects that would once have been labelled as broadcast technology,” he says. “And with the software integration of powerful [virtual] authoring tools like Notch, Unreal Engine and Unity, the circle of convergence has widened even more.”

CONVERGING MARKETS

A primarily broadcast-focused manufacturing group that has also benefited from these converging markets is Evertz. Known for a wide range of products – including contribution and distribution systems, control and monitoring units, encoding/decoding/multiplexing technologies and fibre transport – as well as now owning audio console maker Studer, the company has seen its routers, switchers and IP gateways being deployed in pro AV.

Dominic Doherty, AV product specialist with the dedicated EvertzAV division, acknowledges “an increase in the crossover between the two sectors”, adding that although there is commonality in the underlying technologies, the applications, users and user expectations tend to be very different between broadcast and pro AV. “The AV sector expects broadcast-like quality and resilience but packaged in a way that is simple to use, intuitive and does not require a senior broadcast engineer to operate it,” he says.

Doherty describes broadcast technology as “influencing” the development of AV products at Evertz, with systems being modified to suit the application. “Products will be adapted for AV in the most part but there is some of it that would be as it is in broadcasting,” he says. “That would certainly apply to the switchers and routers, while the IP gateways would be developed more in parallel. There’s two aspects to it: the switchers and routers would be more of a fast follow-up with the broadcast products and the AV gateways would be developed for AV-type applications as opposed to just incorporating broadcasting features.”

Doherty describes broadcast technology as “influencing” the development of AV products at Evertz, with systems being modified to suit the application. “Products will be adapted for AV in the most part but there is some of it that would be as it is in broadcasting,” he says. “That would certainly apply to the switchers and routers, while the IP gateways would be developed more in parallel. There’s two aspects to it: the switchers and routers would be more of a fast follow-up with the broadcast products and the AV gateways would be developed for AV-type applications as opposed to just incorporating broadcasting features.”

EvertzAV offers essentially AV over IP (AVoIP) systems for varied applications, including lecture halls, corporate institutions such as banks and the military sector, which necessitates secure connectivity. “In a podium situation, such as a classroom, lecture hall or presentation theatre, you would have a number of pieces of gear, at the front of the room with the podium or teacher’s desk,” comments Doherty. “It could be as simple as the ability for them to switch between their laptop screen or local PC screen or a video source like a camera. That would be routed through the system to a large screen monitor, for example. Another typical use you see more in AV is the KVM application, where I could be sitting at a single desk and be able to switch between multiple servers.”

VISUAL PRESENTATION

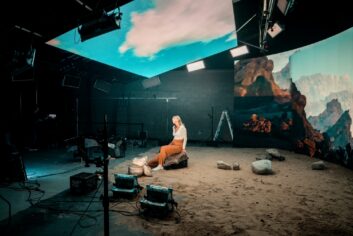

In the area of visual presentation, broadcast companies have been using large format displays and LED video walls on-air over the last 20 years, particularly in news programmes as a backdrop to the bulletin. The increasing use of LED volumes for virtual sets is now offering TV drama producers and filmmakers more flexibility and creativity as a replacement for back projection and green screen, while AV productions are also exploiting the technology. LED manufacturer Absen sees its products used by both broadcasters and AV specialists. The company’s director of virtual production, Brian Macauto, observes that “the technology used in the broadcast world is constantly influencing the world of professional AV”, particularly with the ever-growing need for content creation in recent years.

“LED walls have changed the way they have been used in the industry extremely quickly,” Macauto says. “Originally, when only low-resolution, large-pixel pitch displays were possible, LED walls were typically used only for large outdoor billboards. Now that extremely high-resolution, low-pixel pitch LED displays are common, with great brightness and colour accuracy, the use of LED technology in broadcast studios and content production skyrocketed. LED technology now has a huge variety of solutions and LED is more affordable. LED is now used in all sorts of applications in AV previously not thought of, greatly due to the crossover with broadcast. For example, corporate boardrooms now use LED backdrops and full video production capabilities along with virtual production.”

“LED walls have changed the way they have been used in the industry extremely quickly,” Macauto says. “Originally, when only low-resolution, large-pixel pitch displays were possible, LED walls were typically used only for large outdoor billboards. Now that extremely high-resolution, low-pixel pitch LED displays are common, with great brightness and colour accuracy, the use of LED technology in broadcast studios and content production skyrocketed. LED technology now has a huge variety of solutions and LED is more affordable. LED is now used in all sorts of applications in AV previously not thought of, greatly due to the crossover with broadcast. For example, corporate boardrooms now use LED backdrops and full video production capabilities along with virtual production.”

An aspect of technology that Macauto highlights as having maintained the divide between pro AV and broadcasting is standards. There has always been a strict difference in specifications and applications between broadcast standards and formats such as SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers), SDI (serial digital interface) and SD/HD (standard definition/high definition resolutions) and their respective AV counterparts VESA (Video Electronics Standards Association), HDMI (high definition multimedia interface) and computer resolutions.

“In years past, they could each remain in their own spaces and crossover was not as common,” he says. “As broadcast sets began to adopt technology based in the computer world, such as large video canvases and green screen/augmented reality, the two different worlds of pro AV and broadcast had to work together much closer. Standards in IP and IT that have developed and work well in both worlds make the crossover much easier and faster. New standards in Video and Audio over IP have been instrumental in bringing pro AV-type media server and graphics processing technology to the workflows and standards of the broadcast world.”

The broadcast world has contributed a vast amount to the standardisation of IP as a media transport mechanism. In particular, SMPTE ST 2110, which standardises professional media over managed IP networks, is regarded by technologists and manufacturers alike as a key factor in the wide-scale adoption of IP video. Similarly, the AES67 Audio over IP (AoIP) interoperability standard has enabled incompatible AoIP protocols such as Dante, RAVENNA and Livewire to work together.

While AES67, which also forms the basis of the audio component of ST 2110 (as ST 2110-30), is also being used widely in AV, the sector still has a need for a more prescribed approach to networking and distribution of video. Broadcast-centric standards such as ST 2110 for video and NMOS (Networked Media Open Specifications) for system management and control, are seen as either over-specified or too complicated for AV applications, particularly in terms of PTP and full linear data formats.

While AES67, which also forms the basis of the audio component of ST 2110 (as ST 2110-30), is also being used widely in AV, the sector still has a need for a more prescribed approach to networking and distribution of video. Broadcast-centric standards such as ST 2110 for video and NMOS (Networked Media Open Specifications) for system management and control, are seen as either over-specified or too complicated for AV applications, particularly in terms of PTP and full linear data formats.

Because of this, AIMS, the AMWA and VSF are working on a standard that will set out specific recommendations for IP networks in pro AV. IPMX has been in development for four years but work continues on the standard, which is intended to take the most relevant elements of AES67, ST 2110 and NMOS to create a tailored solution for pro AV.

A large proportion of the building blocks of IPMX has come from the broadcast world. IPMX is based on tried-and-tested broadcast standards such as ST 2110 and NMOS. The aim of IPMX is to work on lower bandwidth networks, whereas, in a broadcast production context, uncompressed signals are transported via 40Gbps, 100Gbps and soon perhaps 200~400Gbps.

Lines blurred then, and as the tech overlaps at IBC and even more so, ISE, are showing, the convergence of AV and broadcast is unlikely to show signs of slowing any time soon.