Bob McCarthy, director of system optimisation at Meyer Sound, offers insights on some of the most noteworthy innovations in concert venue sound, as well as the on-going battle with the structural choices of “architects gone wild”.

Do you think acoustic systems such as Constellation have made truly multipurpose concert venues achievable?

I can confirm this to be the case. Halls can be made with low reverb times and be suitable for high-level concert applications that benefit from tight bass. Then Constellation can add as much reverberation as is needed to accommodate other types of programme. The multipurpose nature can be exploited on a moment-to-moment basis as well, adapting between songs. We have seen a concert at one such hall that ranged from high-level rock (low RT), Broadway revue (medium RT) to unamplified classical (long RT).

We have houses of worship that can range from settings optimised for voice transmission, modern devotional rock music as well as choir, organ and congregational sing-along (mercifully long RT).

This is both practical, economical and provides highly favourable acoustical conditions for the sound systems. The type of reverberation that Constellation creates is spectrally neutral and free of spectral reflections and flutter. Constellation is far more flexible are wide ranging than physical variable acoustics and can deploy changes at the press of a button without mechanical noise or a crew call.

Modern trends are bending toward more realistic concert hall shapes and physical acoustics that more closely fit the real world production needs

Are the often short timescales for concert venue installs ever inhibiting to the implementation of a comprehensive system like Constellation?

There have been portable Constellation systems that provided a virtual acoustic band shell for symphonic performances in arenas (Star Wars in Concert) but this is not the norm. Obviously installing a full Constellation system takes more time, co-ordination and budget than hanging a PA. Constellation is adding a room to the room with typically more than 100 speaker and microphone locations along the walls and ceiling.

The best-case use is when Constellation is planned into a new facility, where it is both cost-effective and can be co-ordinated with the physical acoustical and aesthetic plans for the hall. This ensures that the physical acoustics provide the best foundation for Constellation to build from (low RT and free of specular reflections and flutter). Compared to physically variable acoustics and the option of building multiple halls, Constellation is a huge bargain. Adding Constellation to an existing hall is naturally more challenging since we have to work around the existing conditions, which may include heritage restrictions and other complications.

Aside from active acoustic systems, what have been some of the biggest innovations in concert venue sound over the last few years?

The biggest improvements in my view are that venue designers and facilities managers seem to have finally realised that there are going to be sound systems; big ones, loud ones and even insane ones either permanently installed or visiting for the night. It is not your daddy’s piano recital where “perfect acoustics” (i.e. many strong reflections since they assume we won’t use a sound system) is the design goal.

The modern trends are bending toward more realistic concert hall shapes and physical acoustics that more closely fit the real world production needs. People are paying more attention to absorption in the fly spaces and ceiling (good things). We are seeing more walls employing some of the stealthy acoustic absorbers and diffusers that do their job without anybody knowing it. Another key feature of modern halls is a proper ceiling infrastructure that supports rigging in a variety of locations. Speaker placement is among the most critical aspects of any installation (portable or temporary) so the importance of good rigging locations cannot be overstated.

What are the trickiest concert venue architectural features and constructions for achieving the desired listening experience?

There is a long list from the category of “architects gone wild” including (but not limited to) glass all over the place, wraparound balconies at inclined angles, floating islands on the side of the room with four seats, deep balconies (where folks can’t see the mains) and thick balcony fronts (that send it all back to the stage). We have to cover every seat. That floating box with four seats requires you to dedicate a private speaker for it and potentially blocks the main PA from reaching seats behind it. All this for four seats. But all this pales in comparison to the damaging effects of an architectural mandate for invisible speakers. When sound is ordered to be heard and not seen it is often neither. When our speakers are forced into soffits way off stage or high above the proscenium, we enter the fight with two arms tied behind our back. These hiding places restrict the coverage, block it with beams and add colourful resonances (no thanks). In the words of Gene Autry, “Don’t fence me in.”

Tell us about a recent installation project that highlights Meyer Sound’s expertise in the concert venues sector.

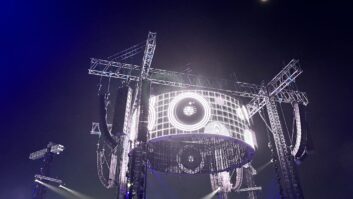

One notable fairly recent installation project was the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles (pictured), a modern symphony hall with acoustics optimised for philharmonic concerts. The bookings however include a great variety of acts including pop and even rock artists. The room has a long reverb time, highly irregular shaping and scattered acoustical reflectors, which complicate the task of providing even coverage over the 360° seating area. The Leopard main system covers around two-thirds of the room and then is aided by a variety of fill systems and delays to tailor the response to fit the irregular shape. A stage deck system (JM1-P) covers the early seating on the ground floor and keeps the sound image focused around the stage. UPQ-1Ps cover the two levels of side seating and a smaller Leopard array wraps around to cover the seats behind the stage. Frontfills, overbalcony delays for the third level and subwoofers complete the system.

Picture: Craig Mathew